Contributor/Collaborateur:Vegas Hodgins

Editor/Révision: Debra Titone

Visuals/Visuels: Fraulein Retanal

We often speak about the gender gap in STEM, but how can we quantify this difference? One method is to look at the number and monetary value of grants awarded at the undergraduate, graduate, postdoctoral, and faculty levels to researchers of different genders. At the 2023 annual meeting of The Canadian Society for Brain, Behaviour and Cognitive Science, WICSC+ co-founder, Penny Pexman and McGill Psychology graduate student Michelle Yang (in collaboration with WICSC+ co-founder, Debra Titone) presented a study which used publicly available NSERC funding data to do just this (following up on Titone, Tiv, & Pexman, 2018, Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology). While this analysis could only account for two binary gender options, it provides a rough sketch of the gender gap in NSERC funding experienced by non-early career women in Cognitive Science. Read ahead for a summary of this presentation and be on the lookout for the full study when it is published!

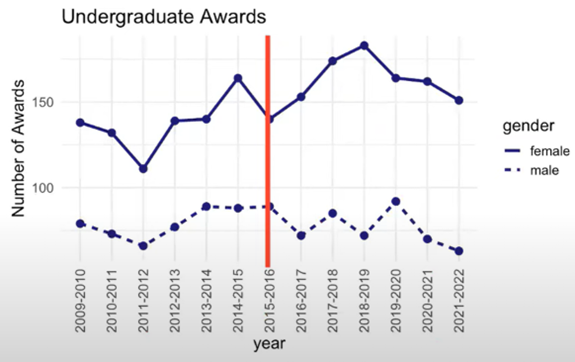

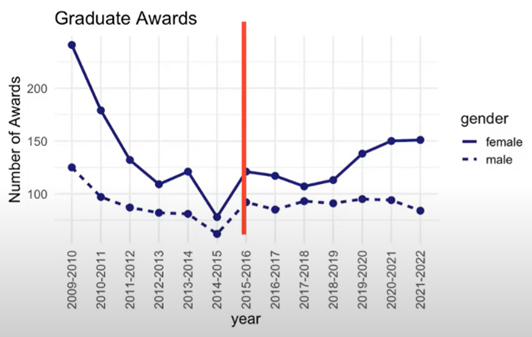

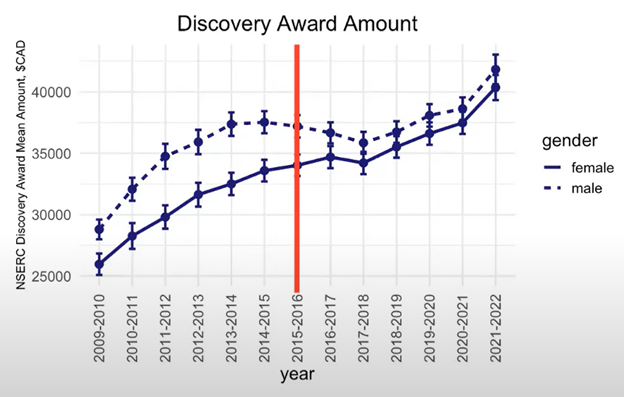

As Dr. Pexman explained, NSERC implemented changes to their Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) policies in 2018 to address inequity in grant funding. As per the Action Plan available here, these policies included EDI training for selection committees, applying EDI analyses to new policies and plans, ensuring that selection committees are themselves diverse, and changes to how research excellence is assessed. The data presented in this project both predate and follow these policy changes. The vertical red line in the following figures represents the year of these changes.

First, Yang described the data at the student level. As can be seen in the figures above, for both Cognitive Science undergraduate and graduate level awardees, more women than men receive NSERC funding. This difference is especially stark in the undergraduate population, in which it may be interpreted that male undergraduate students are at a disadvantage. Alternatively, Yang proposed that this disparity is related to the greater number of women enrolled in Cognitive Science fields at the undergraduate and graduate level. These data also show growth in the number of awards granted to women in the past six years.

Yang went on to describe the data at the postdoctoral level. For postdocs, we again see the trend in previous years indicating more women than men receiving grants, with growth for women from 2016-2017 to 2019-2020 and a drop for men from 2016-2017 to 2017-2018. However, from 2020-2021 onwards, an equal number of women and men received NSERC postdoctoral fellowships, indicating parity.

Overall, in students and postdocs we see a trend which appears to favour women in NSERC funding. However, this trend does not continue once students and postdocs go on to receive faculty-level positions.

As can be seen in the above figure, male professors receive more NSERC Discovery awards than female professors. Over the past six years, awards to women have increased, while awards to men have stayed stable. This suggests that while EDI efforts implemented by NSERC are indeed having an impact on the number of female faculty members who receive funding, we still have yet to reach parity. This lack of parity becomes especially apparent when we look at non-early-career researchers, as can be seen in the figure below.

As these data demonstrate, Yang stated that the lack of parity between male and female faculty awards especially impacts non-early career female researchers. Yang proposed that this finding, along with the findings at the student level, indicate that EDI changes implemented by NSERC have been more effective at increasing the number of female students and early career researchers who receive funding, but have left female non-early career researchers behind. This may be due to non-early career female researchers having been historically denied funding to a greater degree throughout their careers, leaving their CVs with grant histories which selection committees may disadvantage in their choices.

In addition to the number of Discovery Grants awarded, we can also look at the monetary value of these grants. These data suggest that EDI policies implemented by NSERC have been highly effective at closing the gap between the monetary value of grants awarded to men and women at the faculty level.

However, we must still keep in mind that these benefits might not be rolling over to non-early-career female researchers, who receive fewer Discovery awards than men. Thus, while there is evidence for a positive effect of NSERC’s policy changes on early-career female researchers, NSERC must concern itself with closing the gap for non-early career female researchers as well.

To conclude this presentation, Dr. Pexman stated that WICSC+ hopes to expand this analysis in future years by including transgender and nonbinary scholars. However, to do so, NSERC would need to release this data about its award recipients, which it does not presently do. Furthermore, WICSC+ hopes to conduct future analyses which concern other marginalized groups including BIPOC scholars, disabled scholars, and first-generation scholars.

In sum, while parity has been promoted at some levels of grant reception by NSERC EDI initiatives, non-early career female researchers remain disadvantaged. Thus, future EDI initiatives implemented by NSERC ought to take this gender gap into consideration and make moves towards repairing it. This Women’s History Month, we at the WICSC+ trainee board encourage you to show your appreciation towards the non-early career female faculty members in your life. While it is no replacement for appropriate financial compensation, letting such an academic in your life know what a positive influence she has had on you and your scholarship could (at the very least) brighten her day. If you found this post interesting, please share it or its accompanying social media post on your social media of choice. You can find us on X or Instagram @wicsc_trainee.